"Natural State," "Unintelligent Individual," and "Sad Tale Pattern": The Evolution of Wild-Raised Children

Going Wild: The Unpredictable Journey of Feral Children

Ever since ancient times, tales of humans living in the wild have intrigued us. From Enkidu, the wild man of ancient Mesopotamia, to Romulus and Remus, the abandoned twins raised by wolves, myths and legends have captivated our imaginations with wild lives outside civilization. Yet, in reality, these stories often paint a grim picture of human survival in the wild, rather than an adventure full of hair-raising exploits.

"A wild child's life is often a tragic one," anthropologist Mary-Ann Ochota, author of the 2017 book Feral Children, points out. "Basically, it's like playing tragic-story bingo."

Tales of the Wild

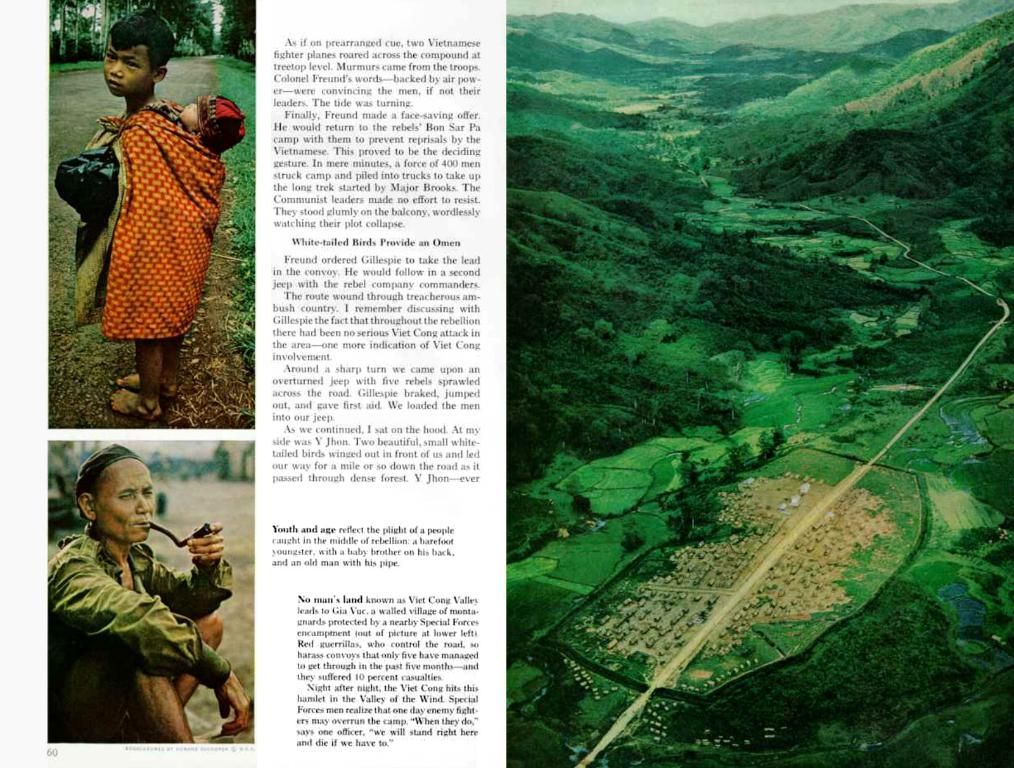

The earliest accounts of "wild" or "feral" children can be traced back to the 1600s with stories of a wolf boy in Germany and the first English tale of John of Liège, a boy lost in the woods who adopted animal-like behaviors to survive for years. Other countries also have their own wild tales, such as Lithuania's wild boy living among bears, Ireland's sheep-raised youth, and German youths raised by cattle. Poland even had an international reputation for children being raised by bears.

Initially, these wild children were viewed with curiosity, mixed with some concern for their souls. Stories were told of their enhanced senses and the difficulty they faced learning to stand and speak. Over time, their perceived humanity was often lost in the process.

With the dawn of the scientific enlightenment, this fascination with wild children turned into what modern scholars refer to as "problematic as &%%$#!" according to 18th century texts. The Enlightenment era saw the creation of six species of humans: Homo americanus, Homo europaeus, Homo asiaticus, Homo afer - that is, American, European, Asian, and African. Then, quite bizarrely, Homo monstrosus - the so-called "monstrous" people, including giants, people with dwarfism, and girls who tight-laced their corsets; and finally Homo ferens - the "wild" people.

Becoming Human

Thankfully, we now know that there is only one human species and "race" is a social construct without basis in biology or genetics. Likewise, individuals with physical differences or disabilities are still simply people, irrespective of their perceived "abnormality."

In the 18th and 19th centuries, scientists and philosophers were captivated by the questions surrounding feral children, debating whether they were soulless animals, unfit to perceive the world, or the purest form of humans, untainted by society's decay.

For Victor, the "wild boy of Aveyron," discovered in France in 1800, both views converged. To French physician Jean-Marc-Gaspard Itard, he was "a living artifact," offering potential insights into whether human knowledge is constructed or innate. To rival physician Philippe Pinel, he was merely an "idiot."

Who was right? At the time, Pinel's claims seemed supported by reality as Victor, despite years of training, could not learn to speak. But was that truly fair? Itard's own notes reveal that Victor had acquired classes, colors, shapes, and an understanding of justice. Had Itard attempted to focus more on developing Victor's gestural communication skills, he might have led a relatively normal life.

Consider the case of Marina Chapman, a woman who claims to have been raised by capuchin monkeys for five years and lacked human language upon her "rescue" at 10 years old. Despite these apparent limitations, she was eventually able to learn two languages, build a normal career and family, and even write a best-selling book about her time in the jungle.

Wild Child

So, why do feral children struggle so much with relearning human skills? Is it because they are innately incapable or is there a more rational explanation?

The most likely answer lies within the latter, though it's uncomfortable to admit that some degree of innate tendency may play a role. "It's possible that some of these children ended up in their strange 'wild' situation due to showing some level of abnormality or developmental delay in the first place," Ochota notes. "In a modern society, it's considered a luxury to raise dysfunctional or disabled children."

Once thrust into the wilderness, their chances of survival were slim. As neuroscientist Heather Stewart explains, "feral children may exhibit the usual range of biological developmental potential, but they fail to develop normal human communication skills as a result of growing up in social isolation without proper models."

A child's brain, particularly during the early years, has remarkable plasticity, but certain skills, like language acquisition, are thought to have a "critical window" for development. If a child hasn't been exposed to human language by the age of five or six, the capacity for acquiring it later may be greatly diminished.

"Humans are social beings by nature," Ochota wrote. "For a child to develop normally, they need others to care for them, to communicate with them, and to keep them safe."

In essence, a child surviving without interaction, language, or love is a damaged child. Humans are not designed to live like that.

Documented Cases of Feral Children

Feral children are extremely rare, with only over a hundred documented cases throughout history. Each case sheds light on the profound impact of isolation on a child's development.

1. Peter the Wild Boy- Found in 1725 near Hanover- Known for his unbreakable silence and animal-like behavior- Contributed to the understanding that language and social skills are heavily influenced by early human interactions

2. Victor of Aveyron- Caught in 1800 in the forests near Lacaune- Studied by Jean-Marc-Gaspard Itard to test theories of knowledge acquisition- His inability to acquire language highlighted the importance of early social interaction for cognitive development

3. Genie- Discovered in 1970 in California- Suffered severe abuse, neglect, and isolation- Her case underscores the critical period hypothesis for language acquisition, emphasizing the importance of early language exposure for proper cognitive and linguistic development

- Feral children, like Victor of Aveyron and Genie, had significant difficulties learning human skills, a challenge that biology and genetics may partially explain. Yet, science and education-and-self-development reveal a more rational explanation: social interaction and love are crucial for a child's cognitive development, especially during the early years.

- In cases such as Peter the Wild Boy and Marina Chapman, the absence of human interaction during their wild years impacted their ability to acquire language and social skills, highlighting the importance of human connection for mental-health and health-and-wellness.

- Despite the struggles faced by these feral children in relearning human skills, learning and growth are not limited by their initial circumstances. With education, support, and compassion, individuals like Marina Chapman have shown remarkable resilience and progress, challenging the limitations imposed by their isolated upbringings.

- Through studying these documented cases of feral children, such as the wolf boy of Germany and Lithuania's wild boy living among bears, we can gain insights into the human psyche, the power of education in self-development, and the profound effects of social isolation on mental and cognitive development.